2. Pitanje: Preveli ste neke od najikonijskih dela zapadne književnosti, uključujući Ašberija, Vitmena i Dikinson. Kako pristupate prevođenju poezije, posebno kada prilagođavate kulturne nijanse sa engleskog na kineski?

Odgovor: Fokusirajući se na Ašberija: ranih 1990-ih, naišao sam na njegovo "Autoportret u konveksnom ogledalu" i bio sam opčinjen. Ranije sam počeo da prevodim "Američku poeziju od 1940." i "Od 1970: ažurirano" za izdavačku kuću Univerziteta Peking Normal — prve kineske antologije postmodernističke poezije, čime sam popunio prazninu. Ašberijeva privlačnost ležala je u njegovom nedokučivom, raširenom stilu i intelektualnoj širini koja je nedostajala kineskom lirizmu. Njegov dekonstruktivni pristup tada je bio stran kineskoj poetici.

Na površini, Ašberijev jezički materijal deluje veoma proizvoljno, stvarajući određen stepen "prepreke" za čitaoce. On naglašava moć umetničke distorzije i odbacuje tradicionalni dokumentarni realizam. Njegove pesme često koriste slobodno-asocijativne slike i primer su postmodernističkog fokusa na proces, često razotkrivajući sam čin poetske kompozicije. On preferira tehnike kolaža, postavljajući materijale iz heterogenih konteksta sa namernom nasumičnošću, što doprinosi čuvenoj nejasnoći i višeznačnosti njegovog dela. Za Ašberija, jezik je i nosilac i prepreka značenju, posedujući dualne atribute otkrivanja i prikrivanja. Stoga, mnoge njegove pesme imaju za cilj da razotkriju složenu vezu između jezika i značenja. Postanak značenja, po njegovom mišljenju, ne potiče od pesnikove subjektivnosti, samog teksta, čitaočevog tumačenja ili spoljnog sveta. Umesto toga, ono proizilazi iz mreže isprepletenih faktora: pesnik, pesma, jezik, čitalac, stvarnost i šire. Ove složenosti nameću značajan pritisak na prevod.

Štaviše, jedan od Ašberijevih najvećih doprinosa lirskoj poeziji leži u uključivanju širokog društvenog rečnika — kolokvijalnog govora, novinskih klišeja, poslovnog i tehničkog žargona, aluzija na pop kulturu i kanonska dela, čak i banalnosti — od kojih su neke teške za dešifrovanje. Njegove pesme nikada ne uključuju napomene, kao da bi kulturne fragmente koje kolažira trebalo da budu univerzalno poznati. Međutim, zbog kulturnih i perspektivnih razlika, dekonstruktivna upotreba kulturno specifičnih referenci zahteva opsežne napore da se iskopaju i rekonstruišu. Ašberijev raširen, duhovit i humorističan stil napreduje kroz "skokove" između fragmenata iskustva na različitim nivoima, što rezultira dislociranim značenjima i lomovima koji iznenađuju čitaoce — zaštitni znak uživanja u njegovoj poeziji. Ipak, ispod ovog humora, ja primećujem podtekst pustopoljine, čak i tuge, koji mora pažljivo da se oseti i u potpunosti prenese u prevodu. Zbog toga, dajem prednost doslovnom prevodu, čuvajući originalnu formalnu strukturu, neologizme i sintaksu, izbegavajući preteranu "domestikaciju". Ovaj pristup olakšava imitaciju jezičkih senzibiliteta dok uvodi nove izraze i leksičke kombinacije u kineski.

3. Pitanje: Vaš prevod "Mobi Dika" je monumentalno dostignuće, sa preko pola miliona prodatih kopija. Šta ste otkrili o romanu što je uticalo na vašu poetsku perspektivu i kako ste pristupili hvatanju njegove dubine na kineskom?

Odgovor: "Mobi Dik" se nalazi među najprodavanijim stranim romanima četiri uzastopne godine, trenutno zauzimajući šesto mesto. Jedno od njegovih otkrovenja za moje pisanje je da je učvrstilo moje uverenje u neophodnost međužanrovskog pisanja — tradicija koja seže od Danteove "Vita Nuove" do Geteovog "Fausta". Još jedan uvid leži u tome kako mi, kao pesnici, razmišljamo o sebi kroz naše odnose sa sobom, drugima, društvom i prirodom. Međutim, ako ostanemo ograničeni na ovaj "ljudski" nivo, teško ćemo shvatiti više istine. Pored ovih horizontalnih veza, moramo uvesti i vertikalnu vezu — od čovečanstva ka božanskom. Tek tada možemo prepoznati da Mobi Dik ne predstavlja samo sirovu moć prirode niti projekciju kapetana Ahabove samovolje, već nadilazi ove simbolične slojeve i ukazuje na transcendentalno postojanje, naime Boga. Uopšteno, širom kultura, poezija se često tretira kao pesnikov subjektivni izliv, izražavajući njegove misli, emocije i volju. Samo pesnici sa čistom verom, svesno ili nesvesno, mogu da prožmu svoj rad višom misijom.

Melvilov stil je kitnjast, čak i ekstravagantan, prepun sugestija, metafora i poetske mašte. Roman je zasićen deskriptivnim detaljima, dramatičnom tenzijom, intertekstualnim materijalom i nadmoćnim simbolizmom. U prevođenju, izbegavao sam previše gladak jezik, ali sam se klonio i arhaičnih dikcija (kao što je kineska verzija Biblije), uspostavljajući ravnotežu između čitljivosti i očuvanja poetičnosti. Svi prevodioci su ograničeni jezičkim normama svog vremena, a ja nisam izuzetak. Savremeni kineski jezik, razređen negativnim uticajima masovne kulture, postao je osušen i osiromašen. Da bih se suprotstavio ovome, svakodnevno sam započinjao prevodilački rad čitanjem odlomaka iz Biblije i književnih zapisa iz dinastija Ming i Qing, nastojeći da spojim ova dva jezička stila. Ova fuzija je imala za cilj da učini prevod gipkijim, nijansiranijim i izražajnijim. Sve u svemu, uspeo sam u ovom poduhvatu.

4. Pitanje: Nazivaju vas jednom od ključnih ličnosti u transformaciji jezika kineske poezije. Kako posmatrate odnos između jezika i evoluirajuće prirode kineske kulture i misli?

Odgovor: Jezik je okvir ljudske spoznaje; on određuje načine razmišljanja. Svetovi koje percipiraju govornici različitih jezika značajno se razlikuju. Bez stranih rečnika uvedenih kroz prevod, nijedna kultura ne može da se zdravo razvija. Uzmimo kinesku kulturu kao primer: višestruki talasi prevoda budističkih spisa i Biblije nisu samo doneli novi rečnik kineskom jeziku, već i nove perspektive i metodologije za posmatranje sveta. Bez pokreta nove kulture karakterisanog uvođenjem zapadnog učenja na Istok, kineska poezija nikada ne bi dostigla svoje trenutno stanje. Ključna odgovornost pesnika je da čuva jezik — ono što se naziva "čistim dijalektom plemena" — posebno kada je jezik sve više oštećen i zagađen masovnom kulturom. Pesnici moraju da održavaju dostojanstvo jezika, jer ispod jezika leži čitav temelj ljudskog postojanja. Kvarenje duše i propadanje društva potiču iz samog jezika. U tom smislu, pesnici su čuvari ljudske civilizacije.

Kineski jezik inherentno poseduje poetske kvalitete; on izvrsno prikazuje konkretn objekte. Međutim, ova karakteristika istovremeno nameće ograničenja — njegova sposobnost logičkog izražavanja ostaje relativno slaba. Stoga, kineska filozofija često oslanja na slike kako bi iscrpila značenje, kao što se vidi kod Laozija i Džuangzija, posebno Džuangzijeva filozofija koja u suštini predstavlja proznu poeziju. U poređenju sa jezicima kao što su latinski, nemački i engleski, kineski se suočava sa većim izazovima u izražavanju složenog logičkog rasuđivanja. Moj doprinos jezičkoj inovaciji leži u mom eksperimentalnom radu koji je kineskom jeziku dao prethodno nepostojeću sposobnost složene samoreferencijalnosti — što predstavlja revolucionaran doprinos.

5. Pitanje: U svom akademskom radu, istraživali ste i kinesku i zapadnu poetiku. Možete li raspraviti o najupečatljivijim sličnostima i razlikama između ove dve tradicije i kako su oblikovale vaš rad?

Odgovor: Moja doktorska i postdoktorska istraživanja bila su fokusirana na uporednu poetiku, ali vaše pitanje je previše široko — zahteva celu knjigu da bi se odgovorilo na odgovarajući način. Ovde ću samo ukratko dotaknuti nekoliko tačaka. Poezija na engleskom jeziku i poezija na kineskom jeziku dele određene usmerene doslednosti. Na primer, obe su se oslobodile metričkih ograničenja: savremena engleska poezija je odstupila od tradicionalnog jambskog metra (posebno u američkoj poeziji), dok je kineska poezija, od Pokreta vernakularnog jezika ranog 20. veka, prekinula veze sa klasičnim kineskim metričkim tradicijama. Ritam i forma više nisu bitne karakteristike poezije. Moderni kineski i klasični kineski jezik su fundamentalno različiti sistemi. U tom pogledu, kineska poezija je bila pod uticajem zapadne poezije.

Naravno, oslobađanje od formalnih ograničenja takođe se dogodilo unutar unutrašnje evolucije kineske poezije — od stroge peto- i sedmo-složne regulisane poezije dinastije Tang, do fleksibilnijih pesama dinastije Song, zatim do labavijih stihova dinastije Yuan, sve do potpunog oslobađanja forme u moderno doba. Vernakularna kineska nova poezija stara je samo jedan vek, nije uspostavila efektivnu tradiciju niti održala kontinuitet sa klasičnim nasleđem — što stvara nezgodnu situaciju u kojoj se njen subjektivni identitet teško učvršćuje. Od 1920-ih, uzastopne generacije pesnika jasno su pokazivale strane uticaje: Xu Zhimo sa britanskim romantizmom, Feng Zhi sa Rilkeom i egzistencijalizmom, Mu Dan sa Audenom, Maglovita poezija ranih 1980-ih sa ruskom poezijom Srebrnog doba, i Treća generacija (moja generacija) sa postmodernizmom, između ostalih. Ovi uticaji služe i kao hrana i kao ograničenje. Što se tiče moje lične kreativne prakse, rezonujem sa tvrdnjom T.S. Eliota — ja sam "klasičar u književnosti" u srži, ali formalno integrišem avangardne elemente. Nastojim da sintetizujem ove dvojne aspekte. Centralna ravnoteža bez pristrasnosti, težnja ka Velikom putu direktno dok se prihvataju svi tokovi — ovo nazivam sintetičkim pisanjem.

6. Pitanje: Vaš nedavni rad, "Istraživanje porekla kineske i zapadne poetike", ukazuje na duboku posvećenost premošćivanju kulturnih i filozofskih podela. Šta mislite da je uloga poezije u olakšavanju međukulturalnog razumevanja?

Odgovor: Podela je definitivno nepremostiva. Kako bih mogao imati toliko energije? Ja samo radim na izgradnji neke vrste duginog mosta. Moj rad, prevodi i istraživanja napravili su revolucionarne doprinose kineskom jeziku u dva aspekta. Jedan je prevod i istraživanje britanske i američke postmodernističke poezije. Većina postmodernih eksperimenata na kineskom je povezana sa mojim prevodima. Antologija američke postmodernističke poezije koju sam preveo je najranija antologija postmodernističke poezije na kineskom, popunjavajući prazninu. Proveo sam 20 godina uvodeći Džona Ašberija na kineski, kao prvi prevod, što je imalo širok uticaj. Drugi aspekt je moj prevod i istraživanje u oblasti ekološke književnosti. Fokusirao sam se na prevođenje i proučavanje tri klasična pisca nakon Toroa u Sjedinjenim Državama: Džona Mjura, Džona Barousa i Meri Ostin. Objavio sam više od 20 svezaka njihovih dela, a Meri Ostin je prvi prevod na kineski.

7. Pitanje: Vaša poezija se često bavi složenim metafizičkim i egzistencijalnim temama. Možete li opisati trenutak ili iskustvo koje je oblikovalo vaše poglede na prirodu postojanja i kako je to uticalo na vaše pisanje?

Odgovor: Suština postojanja, bilo da je to postojanje sveta ili postojanje naših individualnih sopstava, u osnovi zavisi od zajedničkog elementa — transcendentalno označenog. "Ideje" i "Jedno" u grčkoj filozofiji, "Bog" u Bibliji, "Dao" u kineskoj misli, ili božanstva i budisti u drugim tradicijama — iako različito nazvani — ipak imaju uporedivost i tačke preklapanja. Ovde bih to sumirao u jednoj rečenici — poezija je prirodni izliv probuđenog praktikanta. (Pro)buđenje znači uniju čoveka i božanskog, povratak Velikoj transformaciji. Ovo je krajnji cilj u kojem poezija služi iskupljenju duše. U tom pogledu, predložio sam razliku na kineskom između "poezije opstanka" i "poezije postojanja". Prva je samo deljenje iskustva, horizontalno kretanje između ljudi, dok druga, pored deljenja iskustva, uključuje vertikalno kretanje — uspon od čoveka ka Bogu. Velika većina pesnika ostaje na nivou "poezije opstanka" tokom celog života; samo izuzetno retki, milošću, uspevaju da se popnu na uzvišeno carstvo "poezije postojanja", što, naravno, zahteva naklonost duhovnosti iznad ljudskog.

Sa šest ili sedam godina, već sam bio duboko zaokupljen krajnjim pitanjima života i smrti — pitanjima koja niko nikada ne može rešiti. To je bio početak mog buđenja. Do trećeg razreda, kada sam imao jedanaest godina, imao sam izuzetno duhovno iskustvo — video sam potpunu istinu univerzuma kroz prošlost, sadašnjost i budućnost. Bilo je to sveto iskustvo koje je izvan moći jezika da ga prenese, nešto što je moglo doći samo kao otkrovenje od najvišeg duhovnog entiteta. Drugim rečima, neka neobjašnjiva i tajanstvena sila pomogla mi je da se oslobodim ograničenja linearnog vremena i postavila me direktno u centar velikog vrtloga kosmosa, koji obuhvata sva vremena.

Moja doživotna potraga za poezijom i učenjem od tada je bio pokušaj da se vratim u taj trenutak konačnog jedinstva sa svim stvarima. Skovao sam termin — "univerzalna sinhronost svih stvari" — da označim ovo transcendentalno stanje. U stvari, mogli bismo ga jednostavno nazvati rajskim stanjem. Stoga, moj pristup poeziji se razlikuje od drugih. Ja ne izražavam samo svoje lične emocije i težnje; umesto toga, služim kao glasnik iskupiteljske moći koja prevazilazi svakodnevni svet. Moj cilj nije svetski uspeh ili književno priznanje — iako ih ne odbacujem — već nešto mnogo više: da budem svetac među pesnicima. Pustinjski pustinjaci su moji uzori.

8. Pitanje: Kao učenjak i pesnik, videli ste promene u globalnim i kineskim književnim pokretima. Šta mislite da je budućnost poezije u Kini, posebno sa porastom digitalnih i eksperimentalnih oblika izražavanja?

Odgovor: Moja perspektiva nije dovoljno široka da obuhvati globalne književne pokrete — moje dublje poznavanje se uglavnom odnosi na anglo-američku književnost. Što se tiče budućnosti kineske poezije, ne usudujem se da tvrdim definitivne izjave, posebno u pogledu njenih površinskih formi. Možda će se spojiti sa multimedijalnom umetnošću, evoluirajući u interaktivnu mrežu multidimenzionalnih izraza koji prevazilaze jezičke granice. Međutim, ovo postavlja ključno pitanje: da li bi takve transformacije fundamentalno promenile suštinu poezije? U krajnjim slučajevima, da li bi ovo dovelo do samonegacije poezije i njenog konačnog raspada? I dalje sam uveren da poezija mora da sačuva svoj ključni identitet kao jezička umetnost dok traga za inovacijama unutar ovog okvira. Kineska savremena poezija i dalje ima ogroman potencijal za rast u uspostavljanju svoje modernosti i postmodernosti.

Njena budućnost leži u tome da postane organski deo svetske književnosti. Iako se često kaže da "ono što je nacionalno prvo postaje globalno", ja bih preokrenuo ovu maksimu: "Samo ono što je globalno može biti istinski nacionalno." Nacionalna književnost bez spoljnih perspektiva postaje samo monolog — baš kao što se ne možemo videti bez ogledala. Nacionalna kultura mora da doprinese smisleno svetskoj civilizaciji. Jedna stvar je sigurna: kineska poezija se nikada ne sme vratiti tradicijama stihova dinastija Tang i Song. Prirodni, društveni, kulturni i jezički temelji moderne i savremene kineske poezije fundamentalno su se razlikovali od onih iz ere Tang i Song. Samo krećući napred, mogu se otvoriti novi putevi.

9. Pitanje: Po vašem mišljenju, kako poezija služi kao alat za društvene promene ili ličnu refleksiju i da li vidite neke posebne odgovornosti za pesnike u modernom dobu?

Odgovor: Jezik utire put za akciju. On je najvažnije sredstvo misli — zapravo, on je sama misao, sam način opažanja sveta. Obnavljanje jezika je preduslov za društvenu transformaciju. Naravno, ova transformacija počinje sa pesnikovim sopstvenim ja i dušom — unutrašnja, tiha ali intenzivna, čak i tragična revolucija — pre nego što se proširi na spoljašnji svet, ili možda se odvija kao istovremena unutrašnja i spoljašnja transformacija. Krajnji cilj naših života leži u buđenju duše. Poezija prvenstveno deluje na individualnu dušu pesnika. U budističkim terminima, ovo se zove "samo-buđenje i buđenje drugih". Poezija nije oružje, ali poseduje veću moć od bilo kog oružja. Sovjetski crvenoarmejci su ispisivali Ahmatovine stihove na svojim tenkovima dok su jurišali protiv fašista. Jits je verovao da simboli mogu uništiti kosmos — iako njegova mistična spiritualnost može delovati pomalo preuveličano, naravno.

10. Pitanje: S obzirom na vaš ogroman opus i dostignuća, šta vas motiviše da nastavite da pišete i prevodite? Da li postoje određene teme ili projekti koje još uvek želite da istražite pre kraja svoje karijere?

Odgovor: Moje poetsko putovanje tek je počelo, ili, kako je Dante rekao, nalazim se "na sredini puta svog života" (i duhovne potrage). Razvijam jedno međužanrovsko delo čije teme odjekuju Odisejevim izgnanstvom i Faustovom večnom potragom. Konvencionalne poetske forme više ne mogu da sadrže ove multikontekste, što ovaj rad čini izazovnim za kategorizaciju — on će sintetizovati razne kineske i zapadne poetske forme, filozofske meditacije, dramske fragmente i elemente memoara. Još jedan projekat na kojem trenutno radim uključuje recipročnu saradnju sa pesnicima različitih jezika kako bismo zajednički objavili dvojezične zbirke. Ja se bavim prevodima na kineski, dok saradnici objavljuju u svojim zemljama. Ovaj model prevazilazi ograničenja jednosmernog kulturnog izvoza/uoza, stvarajući obostranu korist.

Strani pesnici ulaze u kinesko čitalačko okruženje kroz moje prevode, dok moj rad stiže do engleskog govornog područja. Prvi završeni projekat je "Ljubav preko granica" sa indijskim filozofom-pesnikom Anandom. Drugi je trio sa grčkom pesnikinjom Evom Petropulu-Lijanu i meksičkom pesnikinjom Žanet Eureka Tibursio Markez, sada dostupan na Amazonu. Treći projekat, "Zhao Ye Bai" ("Noćno osvetljavajuće belo"), koautorstvo sa britanskom pesnikinjom Helen Plets, je završen i u procesu finalnog uređivanja. Četvrta saradnja sa američkim pesnikom Aleksom Džonsonom je trenutno u toku. Mi pesnici različitih jezika treba da se udružimo kako bismo srušili Babilonsku kulu jezika i postigli univerzalni sklad kroz poeziju.

6. 3. 2025.god.

Interview with Yongbo Ma for Area Felix,

Conducted by Maja Milojković

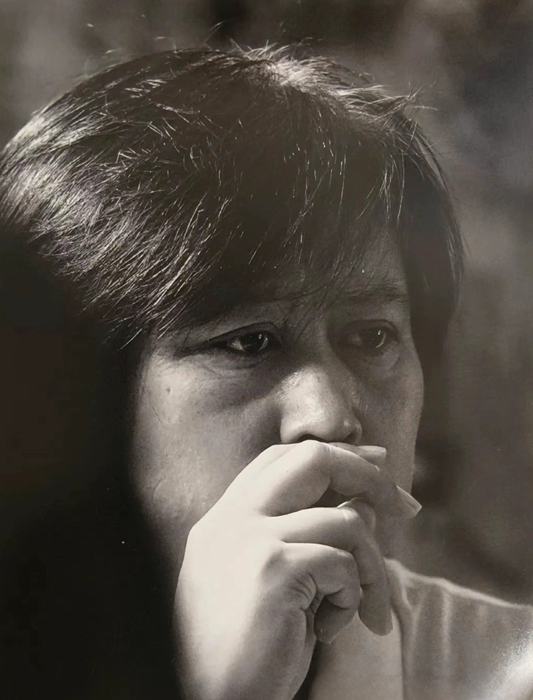

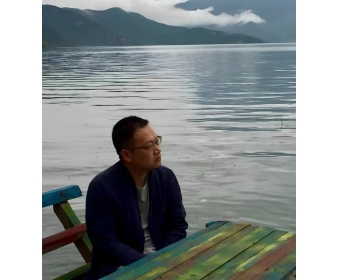

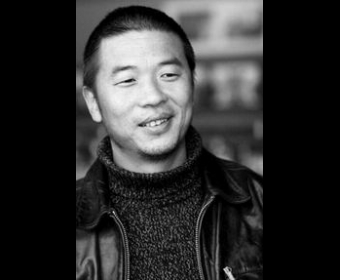

In an exclusive interview for AREA FELIX with Ma Yongbo, we present 10 questions that shed light on his unique contributions to Chinese poetry and his role as a translator. This conversation offers an insight into his rich career, creative processes, and philosophical reflections that shape his work, as well as the challenges he faces in translating poetic works across cultures. Through his answers, you will discover the profound connection between art, philosophy, and linguistic creation, which makes his work exceptional and inspiring.

1. Your poetry has evolved over the years, incorporating elements of postmodernism and deconstruction. Could you share how your creative journey began, and what was the most significant turning point in your poetic style?

YM: From 1983 to the mid-1990s (a decade), I advocated a narrative poetics centered on the presentation of complex individual experiencesto counterbalance—or more precisely, recalibrate—the overpowering lyrical tradition in Chinese poetry. This aimed to achieve a "transitive" quality in poetry, pioneering the exploration of experiential poetics. By emphasizing narrative-driven experiential poetics, I sought to counter the excesses of romanticist lyricism. As a primary advocate of experiential poetics in Chinese, my work did not reject lyricism outright but balanced it with experiential depth. At heart, I remain a lyrical or metaphysical poet. Key works include Return (1983), Kafka (1986), Autumn, I Will Grow Weary (1986), A Chilly Winter Night Going Alone to Watch a Soviet Film (1987), A Walk with the Spirit (1990), Xiao Hui (1994), and Cinema (1996).

From the mid-1990s to the late 20th century (five years), my focus shifted to deconstruction. Observing that the generalization of "narrative" led to solipsism and spiritual stagnation, I recalibrated narrative poetics by proposing "pseudo-narrative" (meta-poetry), aligning with postmodern self-reflexivity. This sought to equalize the creative subject with all existence, exposing narrative contingency, historicity, semiotics, and self-referentiality while laying bare the world’s fragmentation. These techniques, as "the authentic way humans observe reality," relate not merely to craft but to artistic conscience. Representative works from this period include Pure Work (1995), Fantastic Collection (1995), Autumn Lake Conversations (1995), Local Reality: Necessary Fiction (1997), Pseudo-Narrative: Murder in the Mirror or Its Story (1998), as well as several dozens of medium-length and long poems from the late 1990s. In 1999, I published two-volume Anthology of American Postmodern Poetry after eight years of hard translation work, which, along with my creative practices, became a foundational source for Chinese postmodern poetry.

In the 21st century, my exploration coalesces around three keywords: difficulty, objectivity, and ecology. Countering the flattening of contemporary desire-driven writing, I critiqued my own postmodern influences and championed "difficulty writing" under meta-modernism, emphasizing spiritual height, experiential breadth, and intellectual depth. This corrective to Chinese poetry’s decline revitalized its essence. I advocate an "objective poetics" rooted in inter-subjective philosophy, process philosophy, and ecological holism, shifting from deconstructive to constructive postmodernism. Key works include the ecological classic the ecological poetry classic Cool Water Cantos (2001-2006), the long poem Even the Most Humble Existence Attempts to Establish Its Own Order (2006), the poetic drama Vita Nuova (1991-2015), and the long poem Pound Cantos(2021).

The most significant shift in contemporary Chinese poetry is the move from fixed ideologies (ideological centrism, enlightenment, deconstruction) to constructing poetry attuned to the interconnectedness of existence itself. As a key figure in this transition, my contribution lies in diversifying linguistic experiments to imbue Chinese with self-referential complexity, enabling it to reflect on itself while engaging the world—a linguistic revolution that will reshape Chinese thought.

2. You have translated some of the most iconic works in Western literature, including Ashbery, Whitman, and Dickinson. How do you approach translating poetry, particularly when adapting cultural nuances from English to Chinese?

YM: Focusing on Ashbery: In the early 1990s, I encountered his Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror and was captivated. Earlier, I had begun translating American Poetry Since 1940 and Since 1970:UPLATE for Beijing Normal University Press—China’s first postmodern poetry anthologies, filling a void. Ashbery’s allure lay in his elusive, sprawling style and the intellectual breadth absent in Chinese lyricism. His deconstructive approach was then alien to Chinese poetics.

On the surface, Ashbery’s linguistic material appears highly arbitrary, creating a certain degree of "obstruction" for readers. He emphasizes the power of artistic distortion and rejects traditional documentary realism. His poems frequently employ free-associative imagery and exemplify the postmodernist focus on process, often laying bare the very act of poetic composition. He favors collage techniques, juxtaposing materials from heterogeneous contexts with deliberate randomness, all of which contribute to the notorious obscurity and polysemy of his work. For Ashbery, language is both a conveyor and an obstructer of meaning, possessing the dual attributes of revelation and concealment. Consequently, many of his poems aim to unravel the intricate relationship between language and meaning. The genesis of meaning, in his view, does not originate from the poet’s subjectivity, the text itself, the reader’s interpretation, or the external world. Instead, it emerges from a web of interwoven factors: the poet, the poem, language, the reader, reality, and beyond. These complexities impose significant pressure on translation.

Moreover, one of Ashbery’s greatest contributions to lyric poetry lies in his incorporation of an expansive social lexicon—colloquial speech, journalistic clichés, business and technical jargon, allusions to pop culture and canonical works, even platitudes—all of which abound, some of which are difficult to decipher. His poems never include annotations, as though the cultural fragments he collages should be universally familiar. Yet due to cultural and perspectival disparities, deconstructive uses of culturally specific references demand exhaustive effort to excavate and reconstruct. Ashbery’s sprawling, witty, and humorous style thrives on "jump cuts" between fragments of experience at varying levels, resulting in dislocated meanings and fractures that startle readers—a hallmark pleasure of engaging with his poetry. However, beneath this humor, I perceive an undercurrent of desolation, even sorrow, which must be meticulously intuited and fully conveyed in translation. For this reason, I prioritize literal translation, preserving the original’s formal structure, neologisms, and syntax, avoiding excessive "domestication." This approach facilitates the mimicry of linguistic sensibilities while introducing novel expressions and lexical combinations to Chinese.

3. Your translation of Moby Dick is a monumental achievement, with over half a million copies sold. What did you discover about the novel that influenced your poetic perspective, and how did you approach capturing its depth in Chinese?

YM: Moby-Dick has ranked among the top bestsellers of foreign novels for four consecutive years, currently holding sixth place. One of its revelations for my writing is that it solidified my conviction in the necessity of cross-genre writing—a tradition tracing from Dante’s La Vita Nuova to Goethe’s Faust. Another insight lies in how we, as poets, reflect on ourselves through our relationships with the self, others, society, and nature. Yet if we remain confined to this "human" level, we struggle to grasp higher truths. Beyond these horizontal connections, we must introduce a vertical relation—from humanity to the divine. Only then can we recognize that Moby Dick represents not merely the raw power of nature nor Captain Ahab’s projection of self-will, but also transcends these symbolic layers to point toward the transcendental existence, namely God. Generally, across cultures, poetry is often treated as the poet’s subjective outpouring, expressing their thoughts, emotions, and will. Only poets with pure faith, whether consciously or not, can imbue their work with a higher mission.

Melville’s style is ornate, even extravagant, brimming with suggestion, metaphor, and poetic imagination. The novel is saturated with descriptive minutiae, dramatic tension, intertextual material, and overwhelming symbolism. In translating, I avoided overly smooth language yet steered clear of archaic diction (like that of the Chinese Union Version of the Bible), striking a balance between readability and poetic preservation. All translators are constrained by the linguistic norms of their era, and I am no exception. Modern Chinese, diluted by the negative influences of mass culture, has grown desiccated and impoverished. To counteract this, I began each day’s translation work by reading passages from the Bible and Ming-Qing dynasty literary sketches, aiming to merge these two linguistic styles. This fusion sought to render the translation more supple, nuanced, and expressive. Overall, I succeeded in this endeavor.

4. You have been called one of the key figures in transforming the language of Chinese poetry. How do you view the relationship between language and the evolving nature of Chinese culture and thought?

YM: Language is the framework of human cognition; it determines modes of thinking. The worlds perceived by speakers of different languages differ significantly. Without the foreign vocabularies introduced through translation, no culture could develop healthily. Take Chinese culture as an example: the multiple waves of Buddhist scripture translations and Bible translations not only brought new vocabulary to the Chinese language, but also introduced fresh perspectives and methodologies for viewing the world. Without the New Culture Movement characterized by the introduction of Western learning to the East, Chinese poetry would never have attained its current state. A poet's crucial responsibility is to safeguard language—what is called "the pure dialect of the tribe"—especially when language is increasingly damaged and polluted by mass culture. Poets must uphold the dignity of language, for beneath language lies the entire foundation of human existence. The corruption of the soul and the decay of society both originate from within language itself. In this sense, poets are the guardians of human civilization.

Chinese inherently possesses poetic qualities; it excels at presenting concrete objects. Yet this characteristic simultaneously imposes limitations—its capacity for logical expression remains relatively weak. Therefore, Chinese philosophy often relies on imagery to exhaust meaning, as seen in Laozi and Zhuangzi, particularly Zhuangzi's philosophy which essentially constitutes prose poetry. Compared to languages like Latin, German, and English, Chinese faces greater challenges in expressing complex logical reasoning. My contribution to linguistic innovation lies in my experimental work that has endowed Chinese with a previously absent capacity for intricate self-referentiality—this constitutes a groundbreaking contribution.

5. In your academic work, you’ve explored both Chinese and Western poetics. Can you discuss the most compelling similarities and differences between these two traditions, and how they’ve shaped your work?

YM: My doctoral and postdoctoral research both focused on comparative poetics, but your question is too vast—it requires an entire book to answer properly. Here I will only briefly touch upon a few points. English-language poetry and Chinese-language poetry share certain directional consistencies. For instance, both have broken free from metrical constraints: contemporary English poetry has deviated from traditional iambic meter (particularly in American poetry), while Chinese poetry, since the Vernacular Movement in the early 20th century, has severed ties with classical Chinese metrical traditions. Rhythm and form are no longer essential characteristics of poetry. Modern Chinese and classical Chinese are fundamentally distinct systems. In this regard, Chinese poetry has been influenced by Western poetry. Of course, the liberation from formal constraints also occurred within Chinese poetry's internal evolution—from the strict five- and seven-character regulated verse of the Tang Dynasty, to the more flexible Song lyrics, then to the looser Yuan qu verses, until complete formal liberation in modern times. Vernacular Chinese new poetry is merely a century old, having neither established an effective tradition nor maintained continuity with classical heritage—this creates an awkward predicament where its subjective identity struggles to solidify. Since the 1920s, successive generations of poets have clearly manifested foreign influences: Xu Zhimo with British Romanticism, Feng Zhi with Rilke and existentialism, Mu Dan with Auden, the Misty Poetry of the early 1980s with Russia's Silver Age poetry, and the Third Generation (my own generation) with postmodernism, among others. These influences serve as both nourishment and constraint.

Regarding my personal creative practice, I resonate with T.S. Eliot's assertion—I am "a classicist in literature" at core, yet formally integrate avant-garde elements. I strive to synthesize these dual aspects. Central equilibrium without partiality, pursuing the Great Path straightforwardly while embracing all streams—this I term synthetic writing.

6. Your recent work, Exploring the Origins of Chinese and Western Poetics, indicates a deep commitment to bridging cultural and philosophical divides. What do you think is the role of poetry in facilitating cross-cultural understanding?

YM: The gap is definitely unbridgeable. How can I have such great energy? I am just doing some kind of work to build a rainbow bridge. My writing, translation and research have made groundbreaking contributions to the Chinese language in two aspects. One is the translation and research of British and American postmodern poetry. Most of the postmodern experiments in Chinese are related to my translation. The American postmodern poetry anthology I translated is the earliest postmodern poetry anthology in Chinese, filling the gap. I spent 20 years introducing John Ashbery into Chinese, as the first translation, which has a wide influence. The other is my translation and research in ecological literature. I focused on translating and studying the three classic writers after Thoreau in the United States, John Muir, John Burroughs, and Mary Austin. I published more than 20 volumes of their works, and Mary Austin is the first Chinese translation.

7. Your poetry often grapples with complex metaphysical and existential themes. Can you describe a moment or experience that shaped your views on the nature of existence, and how that influenced your writing?

YM: The essence of existence, whether it is the existence of the world or the existence of our individual selves, fundamentally depends on a common element—the transcendental signified. The "Ideas" and the "One" in Greek philosophy, "God" in the Bible, the "Dao" in Chinese thought, or the deities and Buddhas in other traditions—though named differently—still bear comparability and points of convergence.

Here, I would sum it up in one sentence—poetry is the natural outpouring of an awakened practitioner. Awakening means the union of man and divinity, a return to the Great Transformation. This is the ultimate realm in which poetry serves the redemption of the soul. In this regard, I have proposed a distinction in Chinese between "the poetry of survival" and "the poetry of existence." The former is merely the sharing of experience, a horizontal movement between human beings, whereas the latter, beyond the sharing of experience, incorporates a vertical movement—an ascent from man to God. The vast majority of poets remain at the level of "the poetry of survival" throughout their lives; only an exceedingly rare few, by grace, are able to ascend to the lofty realm of "the poetry of existence," which, of course, requires the favor of a spirituality beyond the human.

At the age of six or seven, I was already deeply absorbed in the ultimate questions of life and death—questions no one could ever resolve. That was the beginning of my awakening. By the third grade, when I was eleven years old, I had an extraordinary spiritual experience—I witnessed the complete truth of the universe across past, present, and future. It was a sacred experience beyond the power of language to convey, something that could only come as a revelation from the highest spiritual entity. In other words, some inexplicable and mysterious force helped me break free from the constraints of linear time and placed me directly at the center of the great vortex of the cosmos, spanning all ages. My lifelong pursuit of poetry and scholarship has since been an endeavor to return to that moment of ultimate unity with all things. I coined a term—"universal synchronicity of all things"—to designate this transcendent state. In truth, we might just as well call it a paradise state.

Thus, my approach to poetry differs from others'. I do not merely express my personal emotions and aspirations; rather, I serve as a messenger of a redemptive power that transcends the mundane world. My goal is not worldly success or literary recognition—though I do not reject these—but something far higher: to be a saint among poets. The desert pillar hermits are my models.

8. As a scholar and poet, you’ve seen shifts in global and Chinese literary movements. What do you believe is the future of poetry in China, especially with the rise of digital and experimental forms of expression?

YM: My perspective isn’t broad enough to encompass global literary movements—my deeper familiarity lies primarily with Anglo-American literature.

As for the future of Chinese poetry, I dare not presume to assert definitive claims, particularly regarding its surface forms. It may very well merge with multimedia art, evolving into an interactive network of multidimensional expressions that transcend linguistic boundaries. Yet this raises a crucial question: Would such transformations fundamentally alter the essence of poetry? Taken to extremes, might this lead to poetry’s self-negation and eventual dissolution? I remain convinced that poetry must preserve its core identity as a linguistic art while pursuing innovation within this framework.

Chinese contemporary poetry still possesses vast potential for growth in establishing its modernity and postmodernity. Its future lies in becoming an organic component of world literature. While it’s often said that "what is national first becomes global," I would invert this maxim: "Only what is global can truly be national." A national literature without external perspectives becomes mere soliloquy—just as one cannot see oneself without a mirror. A national culture must contribute meaningfully to world civilization.

One thing is certain: Chinese poetry must never revert to the traditions of Tang and Song dynasty verse. The natural, social, cultural, and linguistic foundations of modern and contemporary Chinese poetry have fundamentally diverged from those of the Tang and Song eras. Only by moving forward can new paths emerge.

9. In your view, how does poetry serve as a tool for social change or personal reflection, and do you see any particular responsibilities for poets in the modern age?

YM: Language paves the way for action. It is the most vital vessel of thought—indeed, it is thought itself, the very mode of perceiving the world. The renewal of language is a prerequisite for social transformation. Of course, this transformation begins with the poet’s own self and soul—an internal, silent yet intense, even tragic, revolution—before it extends to the external world, or perhaps unfolds as a simultaneous inner and outer transformation.

The ultimate purpose of our lives lies in the awakening of the soul. Poetry primarily acts upon the individual soul of the poet first. In Buddhist terms, this is called "self-awakening and awakening others." Poetry is not a weapon, yet it holds greater power than any weapon. Soviet Red Army soldiers inscribed Akhmatova’s verses on their tanks while charging against fascists. Yeats believed symbols could destroy the cosmos—though his mystical spiritualism may seem somewhat exaggerated, of course.

10. Given your vast body of work and accomplishments, what drives you to continue writing and translating? Are there specific themes or projects you still wish to explore before your career concludes?

YM: My poetic journey has just begun, or as Dante declared, I find myself "midway through my life's journey" (and spiritual quest). I have been developing a cross-genre work whose themes resonate with Odysseus' exile and Faust's eternal seeking. Conventional verse forms can no longer contain these multi-contexts, making this work challenging to categorize—it will synthesize various Chinese and Western poetic forms, philosophical meditations, dramatic fragments, and memoir elements.

Another ongoing project involves reciprocal collaborations with poets across languages to co-publish bilingual collections. I handle Chinese translations while collaborators publish in their home countries. This model transcends the limitations of one-way cultural export/import, creating mutual benefit. Foreign poets enter Chinese readerships through my translations, while my work reaches English-speaking audiences. The first completed project is Love Across Borders with Indian philosopher-poet Anand. The second is a trio with Greek poet Eva Petropoulou-Lianou and Mexican poet Jeanette Eureka Tiburcio, now available on Amazon. The third project, Zhao Ye Bai (Night-Illuminating White), co-created with British poet Helen Pletts, is undergoing final editing. The fourth collaboration with American poet Alex Johnson is currently in progress. We poets of different tongues should unite to dismantle the Babel Tower of languages and achieve universal harmony through poetry.

March 6–10, 2025

再见重庆 评论 马永波接受塞尔维亚AREA F:厉害

再见重庆 评论 马永波接受塞尔维亚AREA F:厉害 爱因斯坦的绵祆 评论 马永波接受塞尔维亚AREA F:牛叉叉

爱因斯坦的绵祆 评论 马永波接受塞尔维亚AREA F:牛叉叉 南方的南 评论 马永波接受塞尔维亚AREA F:厉害

南方的南 评论 马永波接受塞尔维亚AREA F:厉害

川公网安备 51041102000034号

川公网安备 51041102000034号